For several years, I supported people with all kinds of text projects as a freelance author, copy writer and ghostwriter: for example, writing concepts, website texts, blog articles or short biographies. Since 2019, the focus of my work has continuously shifted to the palliative care sector. I now work almost exclusively as a story nurse and palligrapher in hospices or on palliative care wards.

People with a terminal illness find in me a trained and attentive counterpart who helps them to trace the common thread in their colourful lives and to create a personal document that reflects the incomparable core of their being.

Heart-centred storykeeping at the boundaries of life

In my old ‘bread and butter’ job writing a ‘nice text’ for my clients was never my main goal – many nice texts are often interchangeable in the end and can be written by almost anyone or by AI. My goal has always been to work together with my clients to find a coherent language for a very individualised offer and the heartfelt concerns associated with it.

Today, I also approach people on the palliative care ward with this attitude: What personal messages from the heart do they want to leave behind for their loved ones when their own heart has stopped beating? What do they want to remain – in the hearts of others, but also on paper?

When I read people their own story, the essence of their life, they almost always say afterwards: ‘You’ve written that beautifully’.

Then I correct them: ‘I just wrote it down – you told it! These are your words.’

My job is therefore similar to that of a midwife: I help to create the words and, through my way of asking questions and listening, support the fact that even at the end of life, something is allowed to come into the world and remain here: a spiritual legacy, told in your own words.

Letting go of the weight of life

Every time I do this, I realise anew that every seemingly ordinary life harbours at least one extraordinary story that is worth being told and safely recorded. Writing down the story of a life does not necessarily mean writing a chronological retelling of all the stages and events. If it is possible to capture the essence of a life lived in the narrator’s own words, then a delicate booklet can be even more powerful than a two-hundred-page autobiography.

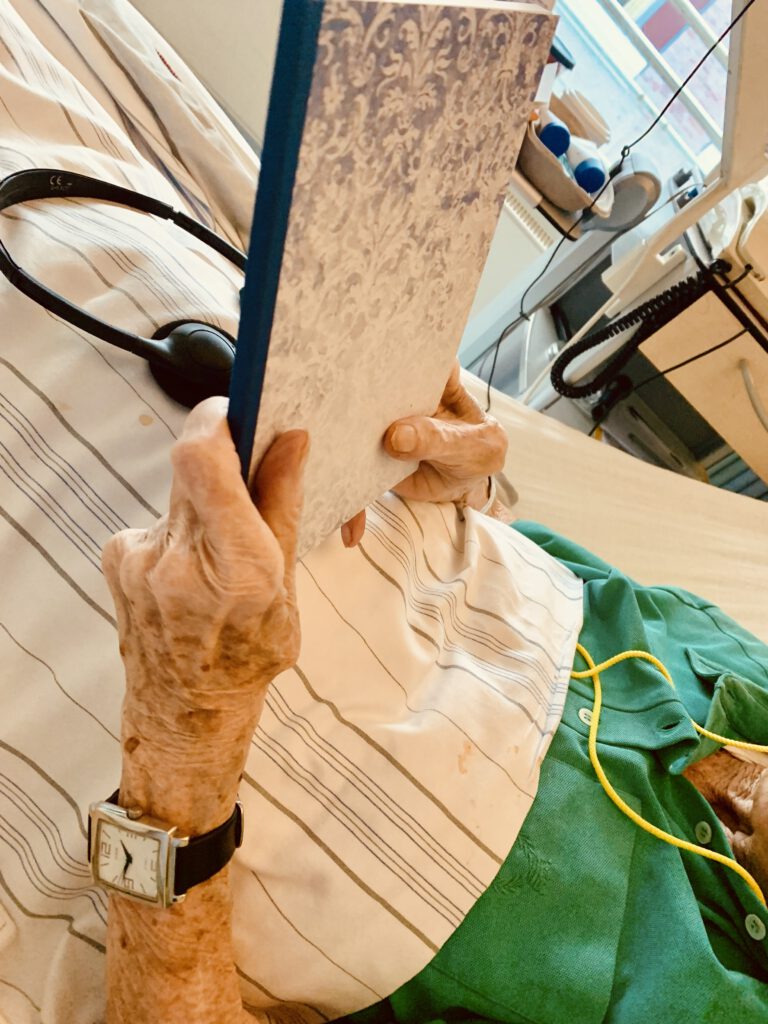

Time and again, I and the medical team observe how people who now literally hold their lives in their hands, securely chronicled and unreachable even for their death, find it somewhat easier to enter the dying process.

What seemed unbelievable and threatening for a long time is now allowed to happen. Also because people not only realise that their life is really coming to an end, but also that it has made a difference to the lives of others and that they will leave their mark.