13 moons

Life in all its facets

The artist Mark-Roger Badel was a patient on the palliative care ward for several weeks and created his palligraphy with me – now he has returned for a very special exhibition

„It happens once in a blue moon“ means that something happens very rarely. The term originates from the 16th century, when people believed for a while that the moon was actually blue. Scientists at the time dismissed it as a bizarre idea, and yet there were occasional, albeit very rare, sightings of a blue moon in various places around the world, e.g. during a volcanic eruption or during a tsunami. This is how the phrase „Once in blue moon“ spread, and eventually it was also transferred and applied to the Gregorian calendar, namely to the months in which there are two full moons in the sky. This happens about every two and a half years.

Why am I telling you this? Well, I have now been recording the biographies of people with a palliative illness for around five years, creating so-called „palligraphies“, and during this time all the people I have met in the course of this work have gradually passed away according to their diagnosis. Except for two. So as things stand now, I could say that every two and a half years someone outlives their prognosis many times over. Once in a blue moon. Like the artist Mark-Roger Badel, who had fallen ill with a rare and usually fatal disease. Excitingly enough, he came to us on the ward in August 2023, the youngest „blue moon“ of our era.

When I met Mark-Roger in the late summer of last year, however, he had no intention of being an exception. But unlike many other people I meet, his desire or hope for „more“ time was not so great. On the contrary, there was even a longing to finally be allowed to „go home“. Because, he told me, he had never really felt „at home“ on this planet. Dying was okay for him, because dying didn’t mean the end of life for him, but just a part of it. Dying is also life, he said, but after death it just goes on somewhere else.

Mark-Roger had already packed his bags, metaphorically speaking, but this experimental trial, for which the doctor at another clinic had registered him more or less unasked, was still standing in the way of his departure. „Mr. Badel, there’s this trial in Hanover, it’s achieving quite good results so far, I’ve registered you for it, surely that’s in your interest!“

But when Mark-Roger came to us on the ward, he wasn’t so sure whether this was really what he wanted. Another lap of honor on this earth, where he felt so homeless, and then almost certainly sitting in a wheelchair, always dependent on the help of other people? He couldn’t really imagine that.

But, as it turned out during our work, somehow this study also appealed to him, namely to be part of a potentially ground-breaking experiment, and – perhaps he didn’t even have to decide, but could let life decide for him. Because he also believed that we humans manifest much more in our lives through our actions and thoughts than we are even aware of.

Perhaps a part of him was still attached to life after all, without Mark-Roger being fully aware of it yet, otherwise this trial would probably not have appeared all of a sudden. And he would probably have been a little more vehement in his opposition to taking part. Besides, and this became the title of his palligraphy, he had „always tried to accept everything that is.“

Mark-Roger did not quit the trial and when he finally left the palliative care unit, I indeed had the feeling that, unlike all the other people whose life stories I had previously recorded, his story was not over yet.

So I was all the more pleased when that call from the early neurological rehabilitation unit came weeks later, and Mark-Roger told me about his progress and his idea to hold an exhibition on the palliative care ward. Of course, I thought, why not?

A few months have passed since that phone call, during which I have visited Mark-Roger several times at his new home, the „At the Hoisdorfer Pond“ nursing home, where he has been living since completing his rehab. And the very first time I was there, in this idyllic place surrounded by nature, I could see a big change in him straight away, it was almost written all over his face: Mark-Roger feels truly at home there, perhaps for the first time in his life.

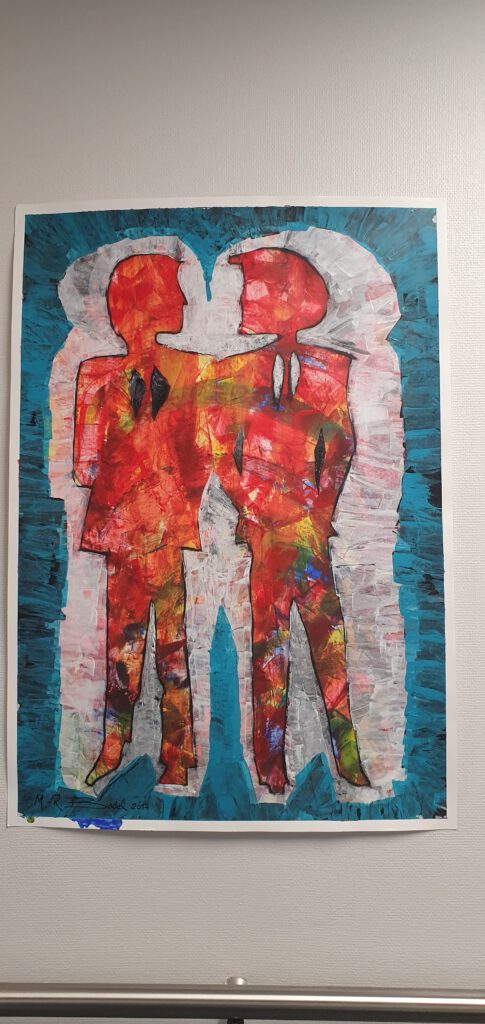

And his soul, which had already been on its way to the „afterlife“, seemed to feel much more comfortable in his body again as well. We can marvel at the proof of this today, because Mark-Roger had started painting again after a break of several months, during which everything had revolved around his illness and the possible departure from his physical life. And he did so with his left hand.

Tentatively at first, then more and more confidently, and above all tirelessly, he practiced with his left hand what his right hand could no longer do due to his hemiplegia. And I am absolutely thrilled at the high level Mark-Roger has already reached in his „left-hand art“, as he affectionately calls his new art.

We selected a total of 26 pictures for the exhibition on the palliative care ward, and I have to admit that chosing wasn’t that easy. In his „previous“ life, Mark-Roger had already painted several hundred pictures, an oeuvre that is second to none. His colorful paintings are always about people looking for their place in this world, relating themselves to life – but also to death. In Mark-Roger’s words, it is about „life in all its facets.“

Together with a patient, the palliative care doctor Julia Fleeth and I finally made the final selection on the ward where we asked ourselves which images could appeal to people in an existential situation, but also to their relatives, on a deeper level. Which motifs are suitable for life on a ward where people also die? Because, this is very important to me, a „resurrection“ like the one Mark-Roger is currently experiencing only happens once in a blue moon.

Most people are denied their great wish for „more time“, and even when a new type of therapy extends life indefinitely, it is an art to make the most of it – to really be in the now and not constantly ask yourself how long it will be okay this time until the next episode of illness hits and with it perhaps really death.

In Mark-Roger’s case, you can even take „art“ literally, because that is exactly what he is now practising every day with unbroken energy and a newfound zest for life. Even though he is in a wheelchair, at least most of the time, because I know that he is now even practicing walking, and I wouldn’t be surprised if, at his next vernissage, he greets his guests standing up again.

So it was always clear that we would only be able to present a limited selection of pictures on the ward due to the space available. I had initially thought of twelve pictures each, twelve of the large ones painted with the right hand and twelve of the smaller ones painted with the left. The number twelve reflects the cycle of the year, and therefore also of life – we have twelve months and – as a rule – also twelve moon cycles.

„But 13 is also a good number,“ said Mark-Roger, because sometimes the year also has 13 full moons, and we both liked the idea that with the number 13 we were also alluding to the extra time that Mark-Roger is currently in, and which he didn’t even know whether he wanted a good nine months ago.

We have decided to hang the 13 large pictures in the corridors of the ward, deliberately without frames, i.e. they can be touched, albeit lovingly and carefully of course, because they were all created using the squeegee art so typical of Mark-Roger Badel. It’s tempting to gently brush over them. In our lounge for patients and relatives, where our piano is also located, there are 13 of Mark-Roger’s new paintings, painted with the left hand. The piano room represents the 13th moon, so to speak, in whose orbit Mark-Roger’s life, his soul and his remarkable work are currently in.

Dear Mark-Roger, it was a great pleasure to plan and realize this exhibition together with you and Julia. Even though I always say that my work doesn’t represent the two percent of people who miraculously survive a normally fatal illness. This is reported in the newspapers and on television, which also filmed your vernissage. With my work, I stand for the supposedly unspectacular stories of the other 98 percent, for the people who die quietly and according to plan, including on this ward. But you have come back here to give these 98 percent and their families and friends a gift. The gift of your touching paintings, which tell of „life in all its facets“ in a very special way, and so often also of dying.

And somehow these pictures also give me courage, because when it comes to dying, we are all in the same boat „in the end“. You communicate with your paintings in a way that is difficult to describe and for which I also lack the words. But good art is also something that shouldn’t be talked about too much anyway.

We would therefore like to invite you to take a look at these wonderful paintings and allow yourself to be touched by them. In this special place, on the palliative care ward of the Asklepios Klinik St. Georg, where many a life story comes to an end, but every now and then, namely once in a blue moon, the beginning of a new story is also written.

More about Mark-Roger Badel <click here>

Annika Röhrs made a film about Mark-Roger for NDR:

https://www.ndr.de/kultur/kunst/hamburg/Mark-Roger-Badel-Von-der-toedlichen-Krankheit-zum-Neuanfang-mit-Links,markrogerbadel100.html